How to remain curious whilst standing up for your beliefs

The Curiosity Mindset series: Part 2

This is the second in The Curiosity Mindset series, a multi-part series of articles going deep on curiosity, the research, the philosophy, and practical tools and methodologies. The first article is here:

“How do I hold my beliefs lightly and with curiosity, whilst still be able to stand up for something important?”

This is a question that several people asked me in response to the first article in this series, and it’s a great question because it highlights two interesting points of tension when thinking about curiosity.

The first is internal: The tension between our ego and our confidence in our beliefs versus remaining open to the possibility that we may be wrong. How do I know if my belief is right? How do I know if I have any blind spots?

The second is external: The tension when our beliefs ‘clash’ with other people and their beliefs. Am I wrong? Are they wrong? Is this the hill for me to die on? But if I don’t stand up for my belief, do I thus stand for nothing?

In both scenarios, curiosity plays a really interesting role because it can be turned inwards on ourselves, and outwards towards those we engage with.

Let’s break it down.

Please note that for this article, I consider ‘beliefs’ to be interchangeable with values, morals, positions, opinions, etc.

How did you come to your belief?

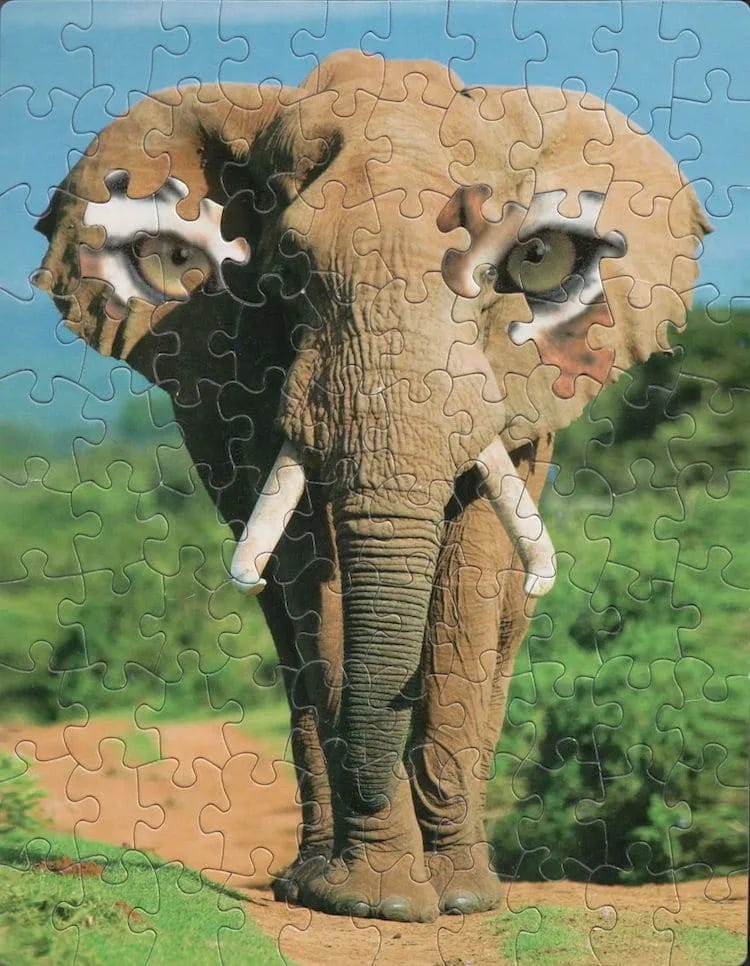

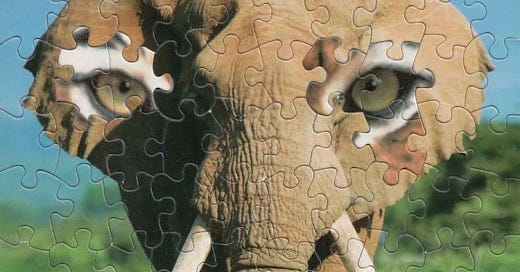

Let’s talk about that internal tension first. In my previous article, I used the analogy of a jigsaw picture to describe how we come to build a belief. Over time, as you collect more pieces of knowledge and experience, you weave them together to form an image that represents your belief.

The interesting thing about puzzles is that once a piece has been added, we tend to stop thinking about how that piece got there; instead we focus on the bigger picture. The same can be said about beliefs.

For example, finish this sentence: “I believe that governments exist to…”

Now, whatever answer you gave, can you recall every single experience or knowledge that contributed to your belief? Sure, there might be a few significant moments that have influenced your picture but I would wager there are many other factors that you have either forgotten or were unconscious of. For instance:

Did you grow up in a socialist country? A monarchy? A republic? A Westminster system of democracy?

What were your parents’ experiences and beliefs?

Do you recall any interactions with government-provided services (e.g. public health care, libraries, regulatory bodies, etc)

Have you travelled to other countries? And if you have, have you noticed how their countries operate?

Consciously or not, these factors (and more) shape our beliefs over time. Children growing up in Western countries might believe that if they behave well enough throughout the year, Santa will give them extra special presents. And even when that illusion is inevitably shattered, an underlying moral belief may persist for many: “Be good, and good things shall come.”

Standing up for our beliefs

The reason I’ve presented beliefs in this way is to make the argument that like it or not, we already navigate the world through our beliefs. Every opinion we share, every idea we express, is an amalgamation of the myriad beliefs we hold.

But how do you know whether that’s true? How do you know if the picture of your elephant is correct?

Prior to the last Australian election, there was a young woman I spoke with who was voting for the first time. She struck me as someone who was quite socially progressive, as she was very supportive of LGBTQI+ rights, climate change, etc. So I was quite surprised when she declared she was planning to vote for the conservative party. To be clear, I didn’t care who she voted for; it just struck me as contradictory.

When I probed her on how she came to that decision, it turned out that she hadn’t researched the history or policies of any political party; she had simply adopted a political position from her parents. By encouraging her to consider how she came to her beliefs—how her image was put together—it triggered a deluge of curiosity (and a fair amount of Googling) that prompted her re-think and re-construct her beliefs.

The point of this story is to highlight three things:

No matter what our beliefs are, it is always worthy of introspection and prosecution. “How did you come to your belief?”

In doing so, we may identify many contributing factors we may not be aware of that influence how our beliefs are formed. “Who / where / what else contributed to your belief? And why?”

And most importantly, by remaining deeply curious about how we came to our beliefs, we can more confidently stand for our beliefs.

Perhaps this explains why people who can explain their thinking are so much more convincing than people who loudly state a position with nothing to back it up.

Loosely held, strong opinions

Turning our attention to the external tension, this is where we experience the ‘clash’ between our beliefs and others. In the best-case scenario, this could be a simple, lively debate. At the worst, this is where we see communication breakdowns, cancel culture, and polarisation.

There is a phrase popularised within the Silicon Valley tech sector: “Strong opinions, loosely held.” I’ll share this handy explainer by Michael Naskin, a VP of Software Engineering at Glow Forge:

The idea of strong opinions, loosely held is that you can make bombastic statements, and everyone should implicitly assume that you’ll happily change your mind in a heartbeat if new data suggests you are wrong. It is supposed to lead to a collegial, competitive environment in which ideas get a vigorous defense, the best of them survive, and no-one gets their feelings hurt in the process.

What really happens? The loudest, most bombastic engineer states their case with certainty, and that shuts down discussion. Other people either assume the loudmouth knows best, or don’t want to stick out their neck and risk criticism and shame. This is especially true if the loudmouth is senior, or there is any other power differential.

Looking at this through the lens of the curiosity described in this article, what I believe is happening is that two people are comparing their beliefs—their images—and arguing over whose belief is ‘better’. When we look across the media landscape, this feels like the debate we see playing out.

Instead, I argue that it would be better to compare how our beliefs were formed. The phrase should read: “Loosely held, strong opinions.” By starting from a position of curiosity first, we can role model several important behaviours:

We demonstrate that we’re willing to show our process of thinking, which invites others to do the same

This helps us better understand how other people think, thus improving empathy

We can drastically lower the heat and move arguments away from the binary nature of who’s right or wrong

We can both learn something and update our respective beliefs as a result

So that’s my belief, backed up by the experiences I’ve had. I’d love to hear from you. Have you had similar experiences when engaging with others? If you had the opportunity to compare beliefs, how did you go about doing that? What happened?

Or for those of you about to enter into a debate, I’d love you to ask: “How did you come to your belief?” and let me know what happens.

Stay curious!

Thanks Scott: Yet another thoughtful and thought provoking article. I was struck by the importance of this line...."like it or not, we already navigate the world through our beliefs". Just the acknowledgement of this, and the openness to consider that my beliefs may not be complete or correct, is important I think. I know that I have held on to certain beliefs in my life that later fell very hard, because of how tightly I held them. Staying open and stable within is a good good challenge. Thanks again Scott.

Okay Scott; this is a goodie. Thank you kindly for putting the effort into such a through provoking article. What came up for me is this - What happens when entire populations are being soaked in on-demand digital media? What happens when this becomes a cultural reference point? Or taken as some kind of surrogate for reality?

Do others observe ways in which this is a vector for pathological social memes or a range of ideologies that do not plug-into our embodied experience aka. 'REALITY'!

(What freaks me out is how the things that happen on social media are now permeating other dimensions of public life and the world of politics.)