Curiosity is not the same as asking more questions

The Curiosity Mindset series: Part 1

This is the first in a multi-part series of articles going deep on curiosity, the research, the philosophy, and practical tools and methodologies. This series won’t be published sequentially; I’ll add to it over time. Enjoy!

The second article is here:

We often hear that curiosity is an important skill to possess. But… what does that really mean?

Let me share a story from my uni days. I’m sitting in a large theatre hall, listening to a 3-hour seminar on Marketing. The lecturer just finished a session on the Value Exchange Model (when a customer perceives value in something that is greater than its cost of production) and was taking questions.

A student raised their hand.

What followed was a barrage of questions (same student) that kept missing the mark: “What if a customer changes their mind? What if a customer wants a refund? What if people like different things?”

After half a dozen questions, it was obvious that the energy had gone out of the room, and we all felt a sense of relief when a second student put their hands up and asked: “How do we influence value as a marketers?”

Before the teacher could respond, someone in the room muttered just loud enough: “Now that’s a good question.”

This moment stayed with me for years. A single question was perceived to be far more powerful than a series of questions. Somehow, it felt like the second student demonstrated greater curiosity. As I’ve wandered deeper into the world of curiosity, I’ve frequently replayed this moment:

Why did we feel this second student demonstrated greater curiosity?

What exactly makes a good question?

Does the volume of questions asked correlate to curiosity?

How do we consider the value of a ‘good question’ relative to the asker? Especially if we also want to hold true to the notion: “There are no dumb questions”.

Why do we ask questions?

No, seriously.

We know what a question is, but have you ever considered why you ask questions?

In my research into the world of curiosity, I’ve found several theories of curiosity. Philosopher and psychologist William James (1899) considered curiosity as “the impulse towards better cognition”; how do we learn what we don’t know? Ivan Pavlov spearheaded research into the spontaneous orienting behaviour in dogs to novel stimuli (“IS THAT A SQUIRREL?!”) as a form of ‘behavioural’ curiosity (Pavlov, 1927).

Psychologist Daniel Berlyne distinguished between the types of curiosity exhibited by humans and non-humans along two dimensions: 1) perceptual versus epistemic (stuff about our environment vs stuff that increases our knowledge) and 2) specific versus diversive (focused vs broad) (Berlyne, 1954).

One of the more ‘contemporary’ theories of curiosity is the ‘information gap theory’, coined by George Loewenstein. His theory states that curiosity arises when we feel a gap “between what we know and what we want to know” (Loewenstein, 1994).

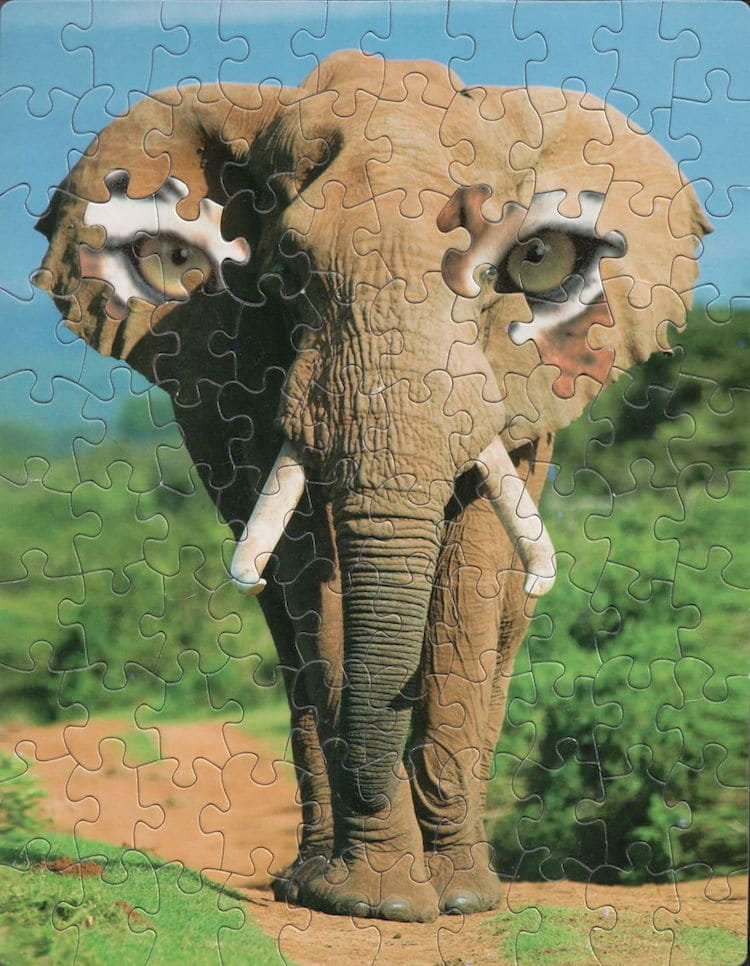

I find it helpful to think about the information gap theory like a jigsaw puzzle. As we go through life, we are building an ever-complex jigsaw puzzle of the world, piece by piece. When a new ‘piece’ of information comes along, it creates a ‘gap’ between that piece and the picture we’re building. This gap triggers a meta-cognitive question: “How does this piece of information fit into my picture of the world?”

By framing it this way, we have a different way of thinking about questions: We ask questions as the byproduct of a gap in our picture, our knowledge. Or put conversely, no gaps, no questions.

Let’s keep building on this.

External information gaps

Imagine you’re sitting with me in that Marketing lecture, and we’re listening to the Value Exchange Model for the first time. What is this new thing? How is it relevant to us? How does it add to our understanding of marketing? Why should we care?

The Value Exchange Model is a new jigsaw piece of information that we don’t yet understand. It creates an ‘external information gap’ that results in a bunch of questions, as we try to figure out how it fits into our respective jigsaw puzzles.

Now imagine a different lecturer walking in. They tell us that the Marketing lecturer is sick, and they’re giving us a completely different lecture on the History of the Library Booking System (no joke, this actually happened). Now, this too is a new jigsaw piece that technically creates an external information gap. And yet… unless you’re a diehard bookworm, $100 says we’re walking out. Why is that?

When you’re scrolling through a podcast library, when you’re in a bookstore, when you’re at a dinner party with strangers, why do some topics put you to sleep whilst others pique your curiosity?

I believe that for our curiosity to be sparked, new information has to be sufficiently relevant to our current jigsaw puzzles. It has to be something that we believe could expand our existing knowledge in some way.

Internal information gaps

I believe there is another source of information gaps, which are the gaps in our existing knowledge.

As we journey through life and as we piece together our jigsaw puzzles of the world, how do we know what we’ve put together is correct? How do we know if our image is accurate? How do we know if our knowledge is ‘complete’ or if there are gaps we’ve glossed over? What if there’s a piece that we’ve put in upside down, which has now warped our understanding of the world?

These are what I refer to as ‘internal information gaps’, and I argue that this is an even more fundamental component of our curiosity.

Simply by reconfiguring what we know of the world, our internal jigsaw puzzles, we can introduce or eliminate gaps completely.

Take this artwork below from artist Tim Klein. Imagine this was your knowledge of how an elephant should look. Because each piece of the puzzle fits so snugly, there is no information gap. This is it. This is the image.

Until that is, you come across a real elephant. Now what? Is the real elephant an anomaly? Or is your image of the elephant wrong?

Assuming you’re reasonable and can set your ego aside, you’ll take out the incorrect pieces, creating the ‘internal information gaps’ that trigger a series of new questions.

In practice, I believe that we navigate life with multiple ‘All-Seeing Elephants’:

We may hold images of the world that aren’t correctly pieced together (i.e. cognitive biases)

Equally, we may have gaps in our knowledge when none need to exist, simply because of how we put our images together (i.e. cognitive blindspot). For example, consider any time you’ve solved a problem simply by talking it out loud

Importantly, ‘All-Seeing Elephants’ don’t stop us from moving forward in the world; the trap lies in being convinced that your picture is perfectly correct

Thus, we can spark our curiosity simply by holding our ideas lightly, and by reconfiguring what we know.

Curiosity ≠ Asking more questions

Let’s return to that uni lecture room and reconsider what it was about the questions both students asked that gave us the perception that one of them was more curious.

As a refresher, the umbrella subject was ‘Marketing’ and the topic taught was the ‘Value Exchange Model’.

The first student asked: “What if a customer changes their mind? What if a customer wants a refund? What if people like different things?”

The second student asked: “How do we influence value as marketers?”

The second student asked a question that — in context of the subject and the other students in the room — demonstrated:

A level of relevance. They asked a question in a way that defined the external information gap between the new topic introduced by the lecturer and the average knowledge of the students

An opportunity for all students to reconfigure their internal knowledge and thus generate new insights

In contrast, whilst the first student asked more questions, they didn’t feel relevant, insightful, or constructive. However, I want to emphasise that this isn’t a criticism of the first student. If anything, their questions may indicate that their jigsaw puzzle of Marketing may be quite poorly configured; an All-Seeing Elephant.

Over to you.

In particular, I’d love to hear: Have you come across people who asked endless questions but you didn’t find them curious? Or people who seemed to demonstrate profound curiosity through one insightful question?

What else do you think contributes to the perception of curiosity?

Thanks for reading.

Wow...now that blew out a few cobwebs! I reckon I have seen many an uncurious person ask endless questions. They often seem to be seeking an answer that confirms their belief, rather than something that just might challenge their belief.

Scott I hope in future articles you might address this: how do I hold my beliefs lightly and yet be able to stand up for something important?

Thanks for a wonderful and deeply thought provoking article Scott.

Yes, this is an excellent blog post and I can think of several people that ask endless questions that do nothing but irritate. Being on the receiving end of this feels like an interrogation or some kind of cognitive strip-search. It is unpleasant and energetically one way. It can also feel like straight out nosiness or worse still coercive.

I like to think of a curious exchange as one that is a two way exchange; like good conversation it is a mutual search for the truth.