Several weeks back, I helped design and facilitate the Regional Mobilisation Summit 2024 in Shepparton (Victoria, Australia), working with Goulburn Murray Community Leadership. This was quite a big experiment; one that I’ve jokingly referred to as the ‘anti-leadership anti-summit’.

In this article, I want to share several notes on what we set out to achieve, some of the big experiments we tried, and a couple of lessons learned on what I could’ve done better as a facilitator.

Setting the scene

Goulburn Murray Community Leadership is an NFP organisation that seeks to foster community leadership in the regional area of Goulburn Murray in Victoria, Australia.

So let’s break down what that means. We’re talking about regional and rural towns with population sizes ranging from thousands to tens of thousands, lots of farming, long distances, many shops that close at 5pm, and largely quite down-to-earth people with a strong relationship with their community.

Community leadership in this context is about activities, initiatives, and actions that benefit the broader community as a whole, addressing challenges specific to those regions. That might come in the form of community organisations, NFPs and charities, businesses, and even informal groups of volunteers.

Leadership in this context is often less about capital L ‘leadership’, and more the ability to bring people together, roll up the sleeves, and get to work with the tools available to them.

The Regional Mobilisation Summit was an attempt to bring together community leaders from across the region, and see if we can kick start a new way of improving collaboration.

The problems we’re trying to address

There were two community challenges we wanted to tackle.

Community governance, succession planning, and evolution: As the broader environment continues to change (I’m talking demographics, technological disruptions, economies, etc), so too do community organisations need to evolve. Old ways of working may no longer be effective.

Evolving community engagement: However, in order to bring in fresh perspectives, we must also make space for them. That can mean letting go of strongly held positions, embracing uncertainty with curiosity, finding common ground, and thus evolving new ways of engaging with each other.

More colloquially: How do we change the way we work, and how do we make space for new ideas that may challenge the way we think?

Hypothesis #1: We don’t need more leadership

Ok, let me unpack this whole ‘anti-leadership’ thing a bit more.

The world of leadership development often focuses on skills, attributes, and behaviours that seek to improve someone’s leadership qualities. As a result, many leadership programs end up focusing on what ‘good leaders ought to be’. Good leaders do this, bad leaders do that.

Yet in all my years across different leadership roles, never once have I thought: “I’m going to leadership today so hard.” When facing challenges, I never think about some 2x2 framework on leadership or pull up a list of leadership behaviours I ought to show.

In fact, I would argue that seeking to become a paragon of leadership can result in worse outcomes because it’s both inauthentic and unrealistic. On the flip side, people might have different expectations of you because you’re considered a ‘leader’ or a C-suite executive.

Furthermore, I argue that the ongoing demand for ‘better leadership’ often translates into a demand for ‘hero leaders’; that one person who can come in and fix everything which is the opposite of community empowerment and collaboration.

That’s not to say there isn’t value in ‘leadership development’ but if we strip away the ‘leadership’ bit, what the vast majority of these programs ultimately achieve is to help people become better people. That we might hold positions of leadership is irrelevant. So… what if we just got rid of the ‘leadership’ bit?

At the Summit, one of the things we experimented with was to ask people to flip their name tags over and write on the other side what they’re passionate about and what skills they can offer. In other words, we asked people to leave their roles and titles behind, so they can show up as individuals.

This is what one person (a Chair of a major community organisation) said when they saw this name tag request:

“Oh how good is this? I get to be a dickhead farmer for the day!”

We had Members of Parliament sitting next to volunteers, business owners next to small charity managers. Not only did we level the playing field with this one simple act, we observed more openness to ideas and perspectives shared around the tables.

Hypothesis #2: We can find common ground

Polarisation is one of the gnarliest social challenges of our time. Typically, it refers to political polarisation and the idea that people are yelling at each other from opposing ends of a spectrum. However, polarisation can also arise when people who have different approaches to addressing problems clash with each other.

I’d like to present an alternative interpretation: Polarisation occurs when people hold on to ideas and positions too tightly, to the exclusion (if not outright rejection) of different ideas.

But we know intuitively that this doesn’t fly; there is never a one-size-fits-all approach to any problem. As all that leadership literature would suggest: Engaging with new perspectives is essential for addressing big problems.

However, something we don’t often consider is how we form our worldviews; the perspectives behind the perspectives. Take a moment and think about ‘climate change’ (relax, this isn’t getting political). Whatever opinion you have on it, how did you form that opinion? Beyond reading some articles or watching some YouTube videos, have you considered your upbringing? Your social circles? Your culture and language? Your educational and work experience? All of these influence your worldview, and thus your opinion.

Now have you considered what other people’s worldviews are?

At the Summit, my good friend Dr Samuel Wilson took the participants through a session that broke this down. For instance, if we stay on climate change, the table below provides three different stories and approaches to addressing climate change, seen through the lens of 3 different worldviews. Importantly, the point is that each worldview is incomplete; it only presents one side of the problem.

We hypothesised that by giving people new lenses and ways of looking at problems that are inclusive of different world views, it might help people stay more open-minded and thus find common ground.

What I found interesting is that through my casual eavesdropping (the real secret trait of any good facilitator), I heard people express how much they resonated with these concepts and how they butt up against these competing worldviews constantly when working with people.

Hypothesis #3: Lowering the gaze

Whenever you get a group of leaders and executives together, invariably people start talking about ‘purpose’ and ‘vision’. I’ve got nothing against a good vision; it’s an important signpost to bring people together and align the work.

The challenge I have is that at this level of discussion, everything becomes a bit wishy-washy. We start debating over esoteric concepts about what ‘a better world for everyone’ looks like, and Summits become an endless talkfest of big ideas.

But… what does ‘better’ look like tomorrow? Next week? Next month? When we return to our work, do we have enough money? People? Skills? When do we actually get time to try to solve the problems we’re facing right here, right now?

This is the ‘anti-Summit’ part I referenced earlier.

We hypothesised that if we brought this diverse group of people together who possess vast reservoirs of skills and experience, and simply give them time and space to talk with each other, perhaps they can help each other solve pressing problems they face right then and there.

Putting it differently, we thought it would be a wasted opportunity to bring so many people together, many of whom have travelled great distances, and just talk at them for the whole day.

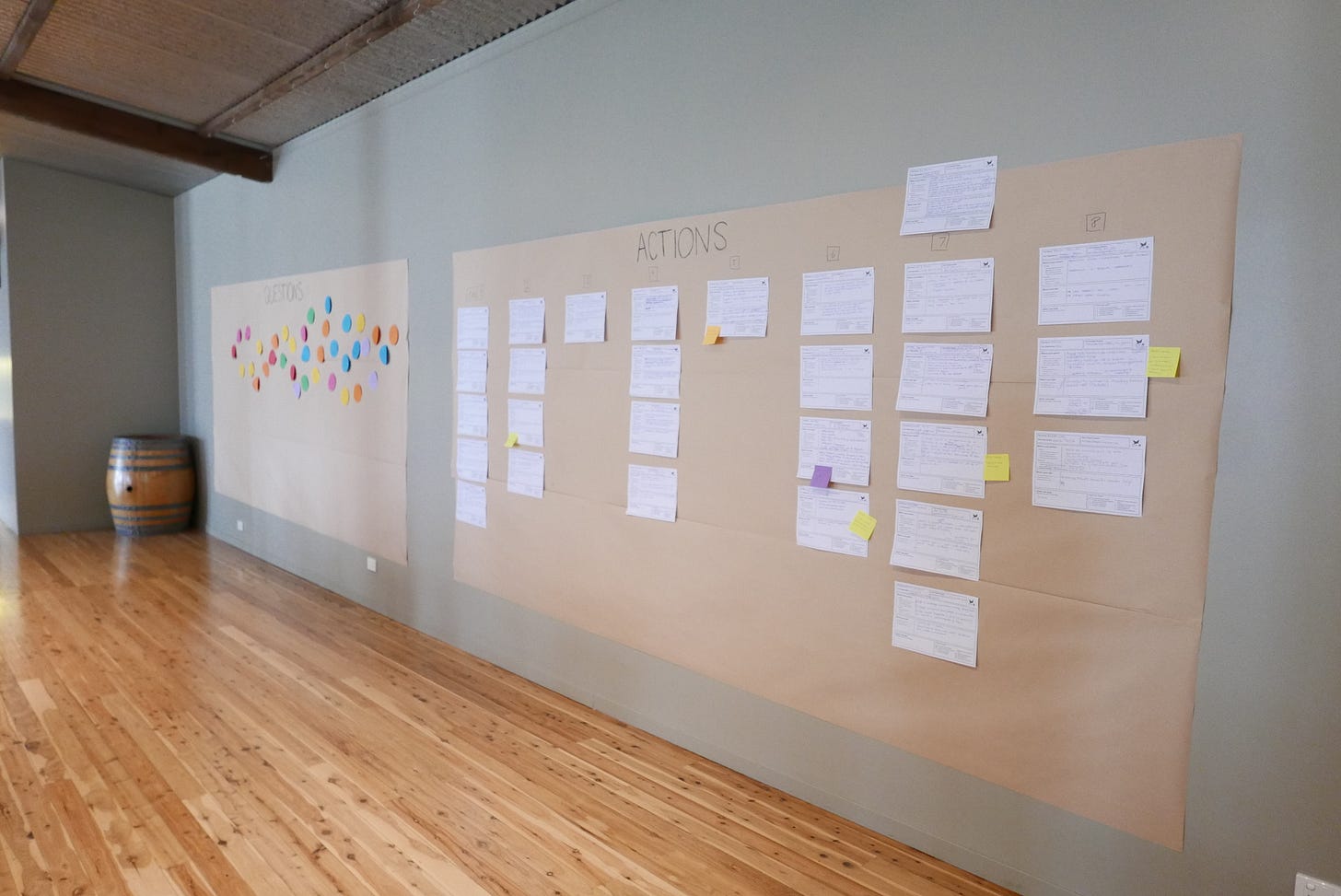

So for a full-day event, half the day was given to the participants to talk among themselves. Naturally, some structure was provided to them so that there was a focal point to the discussion, but the emphasis was on giving people space to figure things out with each other.

At the end of the discussions, we asked each delegate to write down what actions they were planning on testing out within the next 3 months, and gave everyone a microphone so they could ask others for help. We then encouraged everyone in the audience to listen closely; if they could help someone, we asked them to get up to make a direct connection with the person asking for help.

Call it a humble brag, but I’m kinda proud of the fact that despite being the primary facilitator, my total speaking time was no more than about 30 minutes, half of which was providing some simple instructions.

How was this ‘anti-Summit’ approach received?

“I never imagined we could approach our community issues in such innovative ways. This summit has opened my mind to endless possibilities.”

What could I have done better

There is one thing I would like to improve on for future ‘anti-leadership anti-summits’, and that’s to give people some guidance on how to ask for help.

The problem was less about people being afraid to ask for help, but “we need help with grant funding” is a bit too broad of an ask, and helping break down what is specifically being asked for would make it easier for listeners to put up their hands.

In closing

I do want to express deep gratitude to Goulburn Murray Community Leadership, and in particular Nathan Bibby (the Executive Officer), for working with me and being willing to embrace a new action-oriented approach to empowering people in the community.

If you made it this far, thanks for reading! I hope this has provided some interesting food for thought, especially for those of you who are also in this space.

If you’re currently putting together a summit, conference or symposium for 2025 and you’re looking to engage a facilitator or an MC, please feel free to book a call with me and let’s have a chat!

I love this Scott and you know I have thoughts hahahaha

The moment people stopped trying to be "leaders," they started actually leading.

Why? Because real community change doesn't need these things -

More vision statements

More leadership frameworks

More hero-leader worship

What it needs -

People who show up as themselves

Problems broken down to tomorrow's scale

Permission to ask for specific help

The most powerful line? "Never once have I thought: 'I'm going to leadership today so hard.'"

Maybe we don't have a leadership crisis.

Maybe we have an authenticity opportunity.

Thanks for sharing your process! Your framework suggests a real shift in how leadership summits can evolve to meet the needs of modern, interconnected, and diverse communities. By fostering a community of practice, you are empowering leaders to support and elevate each other, moving away from a one-size-fits-all approach that often fails to address specific challenges and opportunities.