Well, saying there’s a bit of uncertainty in the air is putting things mildly, isn’t it?

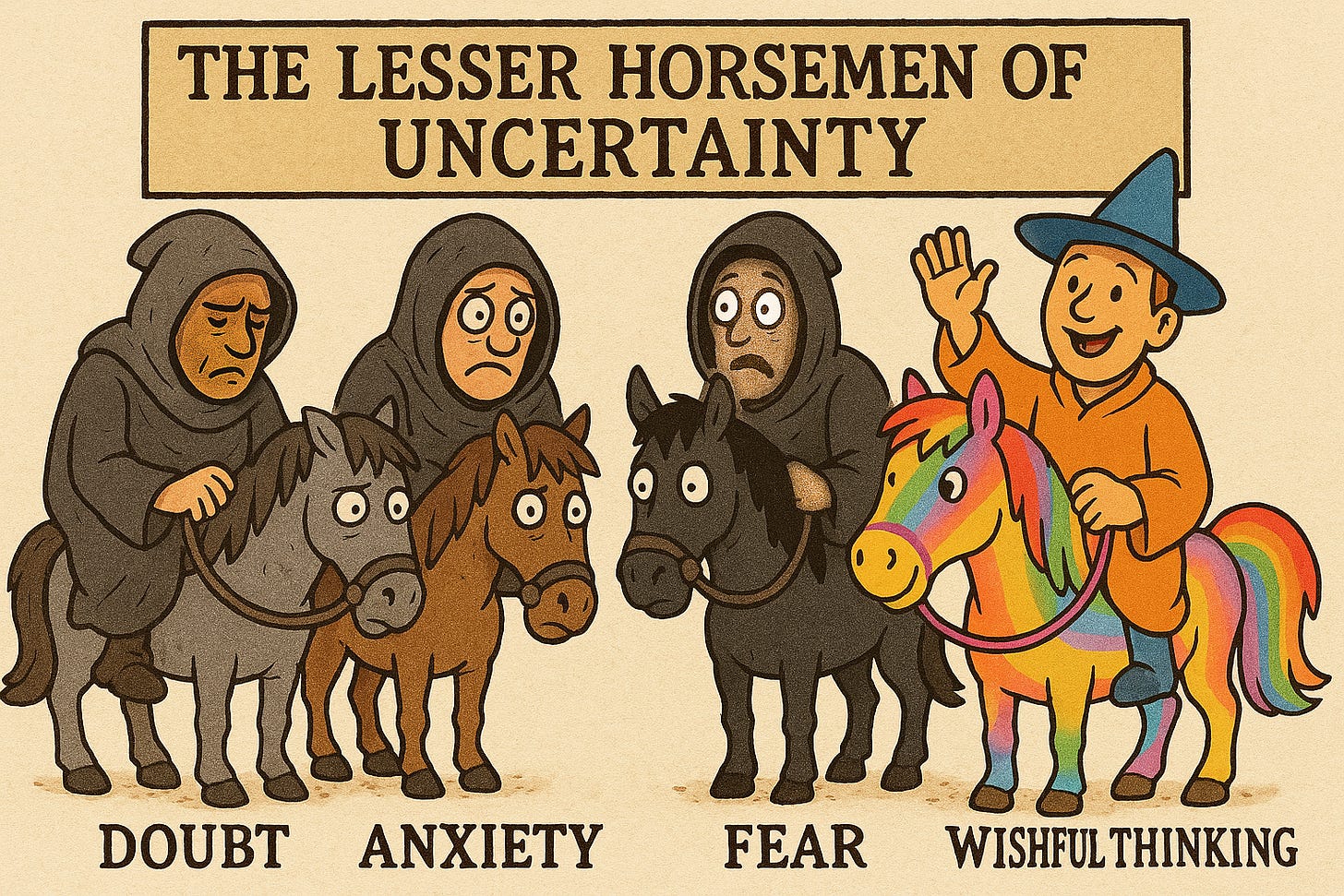

I don’t think I need to spell out all the drivers. Regardless of the source, the simple fact is that we’re in a time of significant ‘wobbliness’, accompanied by the 4 lesser horsemen of Doubt, Anxiety, Fear, and Wishful Thinking.

In this article, I want to take a deeper look at the notion of uncertainty and share a tool I presented at a recent workshop I facilitated on Growth and Curiosity Mindsets that might be helpful.

Reframing uncertainty

First, let’s quickly consider what being in a state of pure certainty means: When we set out to do something, we know exactly what the results will be. We clearly understand what all the variables are, we can predict with full confidence the outcomes of our actions, and it’s something we can repeat consistently.

Of course, this state of being is impossible. The problem with variables is that they are variable. Even a team of the greatest scientists and engineers can’t, with 100% certainty, place a rocket on the moon. But what they do have is a great deal of expertise, built on a foundation of established physics, maths, and research that helps them create extremely accurate models of prediction, that minimise the chance that something goes kaboom.

In a previous article, I presented the idea that one way of thinking about life is as a series of completely random datapoints; an endless universe of stars. To make sense of these datapoints, we build ‘constellations of knowledge’, patterns of thinking, and heuristics that we can apply to this sea of data to make sense of it.

Consider this: You learnt from a young age that you shouldn’t stick forks into toasters. Why didn’t you also need to learn that you shouldn’t stick spoons and knives into toasters? How about sticking a knife into a power socket?

Once we have a ‘constellation’, we possess the ability to apply that heuristic to other datapoints that we come across. We can be introduced to a completely foreign electricity-based device, and reasonably infer that we probably shouldn’t stick forks in them either.

This lets us reframe uncertainty in the following way: Our previous ‘constellations of knowledge’ can no longer be reliably applied to new data points. Putting it a bit more simply: What we knew no longer applies.

Or does it?

The problem with being an ‘expert’

Why do you engage experts?

Well, the simplest answer is that experts are supposed to be good at helping us solve the problems we encounter. They’re expected to possess a wealth of knowledge in a particular field, accompanied by a library of constellations that help them make sense of random data.

For example, a doctor possesses a wealth of sheer medical knowledge, along with the ability to look at the symptoms we present (the ‘random data points’) and then apply a ‘constellation of knowledge’ to diagnose the problem and a course of action.

In business, in our careers, in life, we are rewarded for being experts. Why wouldn’t we be? It’s the essence of getting good at something. It’s why we don’t allow randoms off the street to conduct surgery on us. If we’re good at what we do, at applying our ‘constellations of expertise’, why would we stop? But therein lies part of the problem.

“To a hammer, everything is a nail.”

As experts, we come to rely on the hammers in our toolkit. This is fine in times of stability, but in times of uncertainty, our expertise can be the very thing that holds us back. They become the guardrails against failure, creativity, and learning, to reference

who left this great comment on my previous article.As always, I’m not here to throw the baby out with the bathwater. I am categorically not suggesting that we should stop trusting experts all of a sudden or doubt our own expertise and knowledge.

But in times of uncertainty, we can’t just rely on ‘what we know’. We have to get better at holding our ‘constellations’ and ideas lightly, to be open to change, and – dare I say – become radically curious.

So what does that look like?

The Awareness Framework

At a Growth Mindset / Curiosity Mindset workshop I ran recently, I introduced a simple framework that I want to share here.

The central premise behind this model is that it’s really difficult for people to look objectively at datapoints without automatically applying our respective ‘constellations’, our expertise, our perspectives, to interpret that data. For example, let’s say the temperature outside is 20 degrees Celsius / 68 degrees Fahrenheit; some people will automatically perceive that’s a warm day, whilst others perceive it’s cold.

However, that’s precisely what I argue we need to get better at to navigate uncertainty; to separate the what from how we perceive it.

I used the analogy of a photographer when introducing this model:

The context is the ‘scene’ that we’re looking at. What’s the environment? What’s happening? Who’s involved? What time of day is it? How can we describe this as objectively as possible, with no subjective interpretations.

The perspective is like the lens and filters on our camera. Through what ‘constellations’ are we making sense of the data? What cognitive biases might we hold? What assumptions are we making? What are our beliefs and worldviews? What other filters or perspectives could we apply?

The self is the photographer. What are we choosing to look at within the scene? Why are we choosing to look at one thing over another? What’s not in frame?

In the workshop, we applied this model within the context of community leadership, but it’s easily adaptable to organisations and businesses. For example:

As you can see, the point of this framework is that you can readily apply it to any scenario you face. It’s a way to loosen our grip on our hammers whilst still honouring our expertise, and remember that there is one fundamental principle at play: We are capable of learning new things. We can form new constellations of knowledge, we can chart new paths, and we can most certainly navigate uncertainty.

Whilst my example above is for businesses, I’d encourage you to give it a crack, ideally on pen and paper (just to go old school). I’d especially love it if you let me know how you go. Did you get any new insights? Did you see things in a different light? What’s something you were able to let go of?

In closing

One of my core values is practice what you preach. For regular readers, you may have noticed that I’ve changed the format of this newsletter from time to time, or I’ve missed the occasional ‘weekly update’. And a big reason for that is because I’m constantly ‘navigating’ where I want to take this newsletter, as per my Awareness Framework.

Yeah, I get that algorithms and audiences love consistency and frequent activity… but why keep doing something if it doesn’t serve a purpose or I don’t think it’s providing something of value to you? It’s why you’ll continue to see evolutions with this newsletter, new experiments, and new ideas.

It’s not called the Curiosity Mindset for nothing. 😉

If you liked this article, I’d really appreciate it if you gave it a like or a repost (for Substack readers) or forward it to others you think this would help (for email readers).

What I’d love more is to know what you think. What does this spark for you? Please leave a comment or reply to my newsletter!

About me

I help leaders and business owners get curious to get clear. I specialise in business strategy, leadership, innovation and entrepreneurship, and education.

Here’s how you can engage me:

Facilitation – Through facilitated workshops, I work with leadership teams to get clear on barriers and cognitive biases to deliver breakthroughs.

Training – I deliver training programs on leadership, innovation, and collaboration.

Coaching – I provide 1:1 business and leadership coaching.

Keynote Speaking – If you’re looking for a keynote to inspire, engage, or (positively) provoke your team or community to empower them to think differently, I’d love to come and give a talk. For all bookings, please contact: info@corporatespeakersaustralia.com.au

Or if you’d like to just have a chat first, hit me up!

Hi Scott, thanks so much for the mention of my comment, I really appreciate that.

I believe my thinking toward ‘experts’ dovetails with yours. I think in general, too many people view ‘experts’ as being the ‘last word’ on a topic. I think the healthier approach is to view ‘experts’ as being the FIRST WORD on a topic.

What I mean by that is, if I see an expert write about a topic, I don’t blindly accept what they write as being the ‘truth’ about that topic. Instead, I will do my own independent research into the topic, based on their writings.

I love Culture Critic’s Substack. When they write about a topic, I view it more as an introduction to the topic, then seek out other sources of information so I can learn more about the topic on my own.

I don’t think the job of an expert is to give us a complete understanding of a topic. I believe the job of an expert is to make a topic MORE ACCESSIBLE.

I was talking about this subject with my son recently, who is studying politics, economics and society. I was saying that it's better to ask questions than to come up with answers too quickly. A growth mindset requires suspension of expectations. But of course there comes a time when we need to make a decision and act. How do we judge when that should be and how much to rely on an open mind and how much on expertise? Excellent discussion and illustrations, Scott.